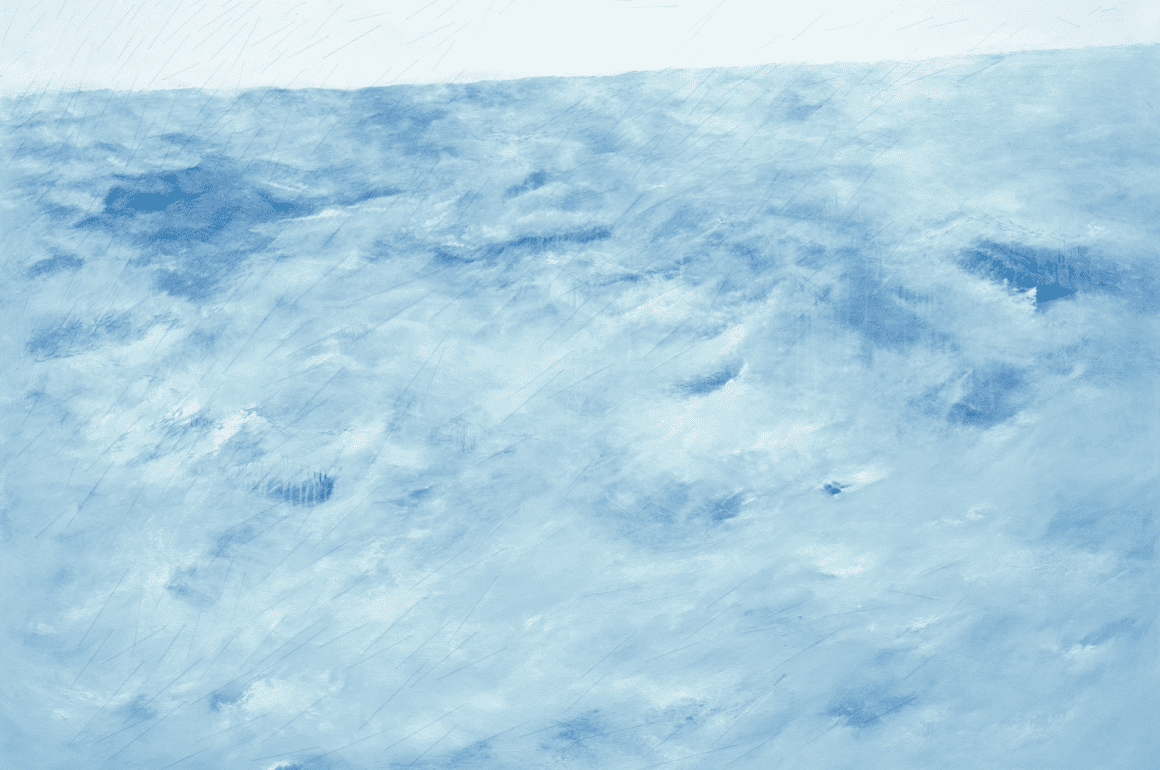

Mongol Zurag painting is the longest living genre unique to Mongolia. Here is a distinctive contemporary artist whose paintings captivate with their mesmerizing detail.

Contemporary Mongol Zurag artist, Gerelkhuu Ganbold, creates modern paintings rooted in Mongolian visual traditions. The subject matter of his paintings challenges the viewer over the question of who holds power in the mysterious puzzle of life, and seems to ultimately ask whether those who are in charge will always remain so.